Standing on the Turkish side of the Evros River on a cold night in early February, the Iraqi family was probably nervous. They were in a difficult familial configuration, a lone father traveling with his five children. They might have been scared, or tired, or bitter, or hungry (or maybe not—maybe their stomachs were twisted in knots, preventing them from even thinking about food). They were also likely hopeful. After all, they were standing at the edge of Europe. They had managed to leave a war-torn country and traverse Turkey. Now Greece, with its promise of peace and human rights, was beckoning from the other side. Along with a half dozen other refugees, they climbed into a dingy plastic boat and set off across the river.

The Evros river has its start in the Rigla Mountains in Bulgaria, snaking down for 300 miles through mountains and valleys and fields before unceremoniously exiting into the Aegean Sea. Aside from a seven-mile stretch of land that was barricaded with a fence in 2014, Greece—and Europe—is separated from Turkey by a thin river no more than three meters deep. At no point is the river so wide that you can’t see the other side. Compared to the stormy vastness of the sea, the river seems manageable for those looking to cross into Europe. We tend to trust things we can see.

And so the Iraqi family crossed the river, Europe in plain view. Along the way, something happened. It’s not clear if the boat was punctured by a floating tree branch, if the weight of the group dipped the boat under the water, or if someone just reached out a curious hand to skim the surface of the black water and tumbled out of the boat. Greek police found the group stranded and shivering on an islet on the river, minus three of the man’s children.

“We really have a problem with children,” Pavlos Pavlidis tells me.

Pavlidis is a forensic scientist. From a fluorescent-light flooded office in the University Hospital of the coastal town of Alexandroupoli, he is responsible for examining and identifying the bodies of dead migrants in Evros. He is the only person in Greece doing this work—a grim occupation since he started in 2000, and one that has become more so in recent years.

The Evros crossing has historically been a point of migration. Most parts of the border are military zones, and until 2010, this area was riddled with 25,000 landmines planted by the Greeks in 1974 after Turkey invaded Cyprus; a common source of both death and injury were exploding mines. Until around 2013, the majority of people entering Greece through Evros were single men, Pavlidis explains, and the death counts were relatively low. With the start of the Syrian Civil War, more families started to come across, and women and children began to die.

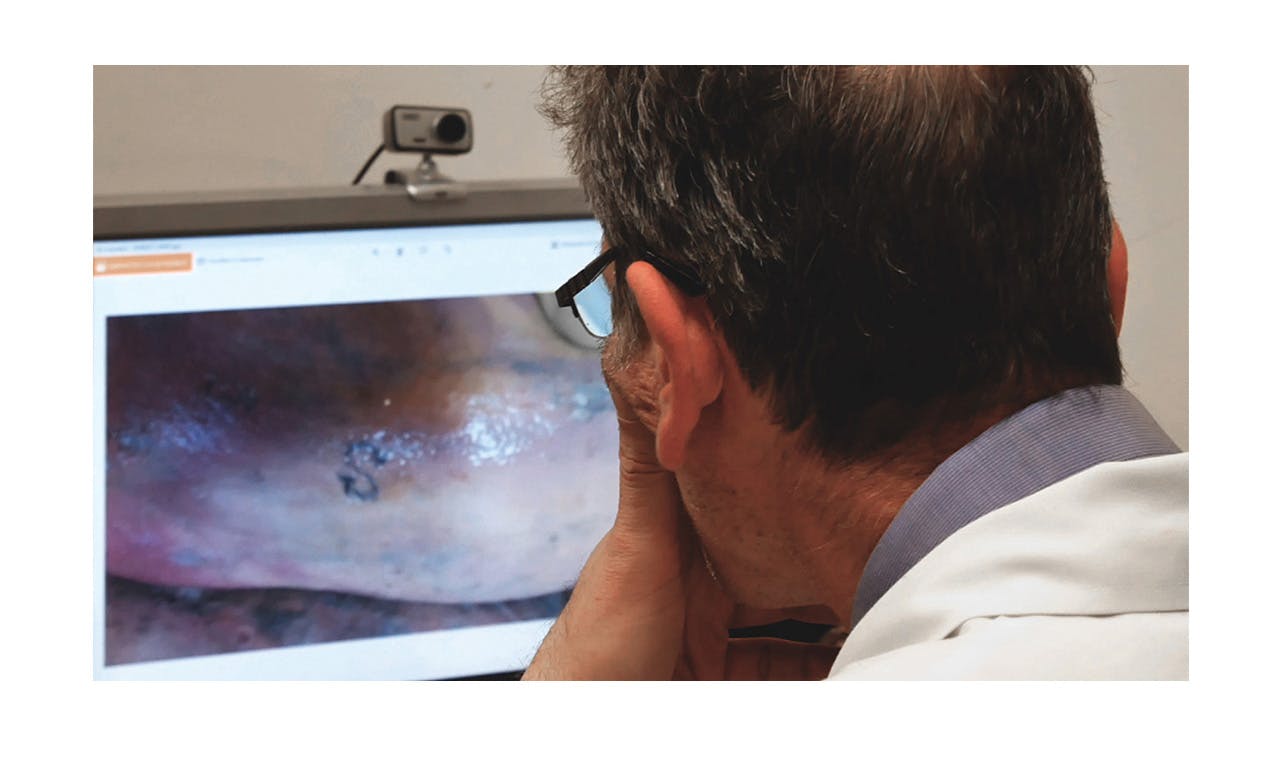

DISTINGUISHING MARKS LIKE TATTOO S CAN HELP IDENTIFY BODIES.

Until 2016, most smugglers took refugees into Europe via the sea route, loading them into boats bound for the islands of Lesvos, Kos, and Samos—a well-documented journey fraught with its own dangers. But an agreement between the European Union and Turkey in March of that year, which allocated €3 billion to send asylum seekers back to Turkey from Greece, reduced sea arrivals. Land routes like Evros were not affected by the deal, and desperate people found alternate paths to the relative safety of Europe. The numbers of interior crossings began to climb back up again. In spring of 2018, a surge of people from Syria and Iraq crossed the border. At the height of the influx, in April 2018, 2,700 people crossed, more than the entirety of crossings in 2017. And by the year’s end, 39 people had died in Evros. (As of March 2019, hundreds have continued to cross, and four people have died.)

Crossing the Evros comes with many risks. Drowning is the most common cause of death, followed by hypothermia. Smugglers don’t allow migrants to bring bags onto the boats, so most people wear several layers of clothing. Even a seasoned swimmer would have trouble navigating the strong current, particularly during the winter months, when the river floods. The muddy bottom of the river is loaded with fallen branches that can snag on clothes and puncture boats. Children lost to the river are almost never found—their small bodies are too easily stuck to the bottom, and the fish quickly eat their flesh. The Iraqi man’s children have not been found, notes Pavlidis, and probably never will be.

“[The] danger doesn’t stop there,” says Dimitris Koros, a lawyer with the Greek Council of Refugees, referring to the many road accidents that happened in 2018. “The smugglers use bad old cars, [with] police chasing the vans, traffickers [will] use some of the refugees as drivers, and sometimes the refugee might be taken in as a driver.” In 2018 there were nine car accidents resulting in deaths of migrants, up from two in 2017.

And there are other hazards, too. One of the most bizarre cases Pavlidis has come across in his career is that of three women who were murdered on the banks of the Evros in October 2018. DNA testing determined it was a mother with her two teenage daughters, though the rest remains a mystery: where they are from, who killed them, and why. Their hands were bound with rope, and their necks slit. Discovered a few days later by a farmer, their bodies are currently languishing in a fridge donated by the International Red Cross (IRC).

The women have not been identified, which highlights a central issue for Pavlidis. Who are these people? He works directly with foreign embassies in Athens, though that’s not always straightforward. Afghanistan doesn’t have an embassy in Greece, for example, and some countries are less than cooperative—it took over two years for the Chinese government to give a response regarding one body. “My problem is contact with the families,” he says.

Instead he has to rely on the bodies themselves, which offer clues. While nationality is nearly impossible to determine, identifying marks or tattoos are useful, and in the case of men, their religion can sometimes be determined by checking to see if they were circumcised.

“Hypothermia is good, because we have a fresh face if we find them. After a few days, we can usually identify them,” says Pavlidis. “Otherwise, it’s normal for the skin to break.” Sitting at his desk, he shows us digital photos of a bloated body, the skin peeled off in sheets and stuck to the metal gurney. Unlike the sea, where the salt can preserve bodies for several weeks, freshwater rapidly breaks down the skin.

After nearly two decades in the morgue, Pavlidis is hardened against the images and smells. “I must be a professional, otherwise I will die of a heart attack,” he says. He’s well aware of how gruesome the photos are, and is reluctant to show them to families. Instead, he meticulously documents each corpse, photographing the body and gathering any objects that are found alongside the body, which he individually bags and puts into cardboard boxes.

GREEK FORENSIC SCIENTIST PAVLOS PAVLIDIS.

“Because of the length of time spent in the water, their personal items or documents are damaged,” he says. It’s also frustratingly easy to lose things: Back in Athens, I meet a Syrian refugee living in a church with his wife and young daughter. They are now trapped in the traumatic bureaucratic cycle of government paperwork, complicated because “the river took all of our documents,” the man explains to me. And if Pavlidis does find documents, like passports, he often discards them as “too easy to forge.” Syrians are more likely to be granted asylum than other Arab-speaking refugees, creating an incentive for such forgery. Misidentification due to fake documents could further traumatize families of the wrongly identified.

As I lift off the top of one box, I’m hit with the heady, masculine scent of cologne (Bara for Men, the label reads). The smell is oddly alive, mingling with all these bagged objects: medicine, jewelry, cellphones and discarded SIM cards, good luck charms, passport photos, condoms, hair brushes, toiletries, chargers, razors, glasses, money, little scraps of paper. Some of the items are already tinged with rust.

Belongings alone aren’t enough to identify a body, and Pavlidis takes DNA samples from each individual corpse, usually from the teeth. Within the migrant community, people know to come to Pavlidis if they fear their family member has died in Evros. He’ll take a DNA sample from the family, and then compare it to his database. So far, he’s identified over one hundred people, and the reunification is a bright if bittersweet relief in his work.

“Each body has a unique identification number, that’s unique to me and the police. If I have a case that comes in after five years, I can give them the location of the body,” explains Pavlidis.

Until two years ago, unidentified bodies were buried in either a local Christian cemetery or in the Muslim cemetery in the village of Sidiro, a Turkish Muslim enclave in the hills of the Evros region. Sidiro is an odd relic of Greece’s history with Turkey, and until the mid-1990s, a permit was needed to enter the village. Muslim bodies sent there were given an Islamic burial by the village mufti. But because migrants from Middle Eastern countries are not uniformly Muslim, it was impossible for Pavlidis to always determine, particularly in the case of women, what religion they were. Now everyone is buried in a non-denominational cemetery on the outskirts of Orestiada, a border town where police are headquartered and the EU border agency Frontex is stationed.

It’s late afternoon when we arrive at the cemetery. A church sits off to the side, and there are two plots full of tombs and newly turned soft soil. I walk quickly along the graves, which are elaborate and adorned with fresh and faux flowers and clearly Greek Orthodox, before realizing that the migrants’ graves are probably relegated to a forgotten corner. I walk to the edge of the church’s land, burrs sticking to the hems of my pants, before finding what I’m looking for: rows of concrete graves covered in white gravel, each marked with a small marble plaque bearing an identification number and a date.

“Regardless of religion or nationality, everyone deserves respect in death,” Pavlidis says.

The graves are surrounded by tall grass, and butt up against a chain-link fence. The sun dips behind the green hills, and the cemetery is awash with lurid shades of orange and pink.

It’s absurdly beautiful.